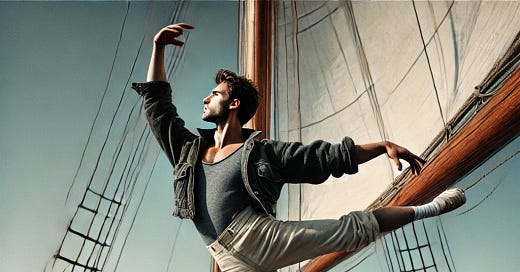

Sailing Beyond the Boat: How Cross-Training (and Ballet!)with Bill Monti Led Me to My Second Laser World Title in 1977

Sailing Beyond the Boat: How Cross-Training (and Ballet!) with Bill Monti Led Me to My Second Laser World Title in 1977

By John Bertrand (USA)

I remember the summer of 1976 vividly. I had just won the Laser Class World Championship, but I felt there was another level waiting for me—something I hadn’t yet tapped into. Like most singlehanded sailors, I did my best to stay fit: I jogged occasionally, did some basic calisthenics, and spent hours on the water. However, I had no structured training program beyond typical on-the-boat drills.

That was when I crossed paths again with my high school physical education teacher and good friend, Bill Monti. Bill was one of those rare individuals who saw the big picture in athletic development. Although Bill initially knew little about dinghy racing, he understood the physical demands and mental endurance required for top-level competition. Bill approached me with a concept that would revolutionize my preparation for sailing: cross-training.

The Genesis of a New Approach

Bill and I began by analyzing every aspect of Laser sailing. On the surface, singlehanded dinghy sailing is straightforward; however, those who have raced a Laser know how punishing it can be. You need the agility of a gymnast, the endurance of a marathon runner, the balance of a surfer, and the strategic thinking of a chess player—all rolled into one. Bill and I broke down these components:

Endurance – The sustained hiking positions and long regattas demanded more cardiovascular fitness than I had ever realized.

Strength—Although the boat is “simple,” controlling the sail and hull through waves in a strong breeze taxes the arms, legs, and core muscles.

Agility and Flexibility – Tacking and gybing in a tight fleet or big breeze can be akin to a dance routine—one misstep, and you’re in the drink.

Mental Toughness – Inevitably, your mind becomes as tired as your body. You need focus to make tactical decisions at the end of a four-race day.

Bill’s vision of cross-training was structured around these fundamentals. Instead of only relying on time in the boat for practice, we developed a comprehensive routine combining running, cycling, and resistance exercises to build a well-rounded athlete capable of withstanding the Laser’s rigors.

Early Skepticism and Breakthroughs

At first, I was excited about breaking new ground but nervous about spending more time training outside the boat than on the water. When Bill mentioned Ballet as a core training component, my commitment to the project was tested until I saw how many pretty girls were in the class!

Bill had me keep meticulous track of my metrics. We measured heart rate, recovery time, flexibility*, and perceived exertion during workouts. Over a few weeks, I began to see patterns emerge. My heart rate recovered more quickly after intense drills on the water. I could hike longer before my legs started trembling. My shoulders felt stronger when pulling in and adjusting the sheets in gusty conditions. Suddenly, the rationale behind cross-training became crystal clear: I wasn’t just developing general fitness; I was building sailing-specific stamina. *At a training camp at the Squaw Valley Olympic Training Center, I tested the most flexible out of all the athletes from the various sports who attended.

Incorporating Ballet Training

One of the most surprising but effective components of my cross-training program was ballet. While it might sound like a strange pairing—ballet and Laser sailing—ballet bolstered several attributes essential for top-level dinghy racing. Under Bill’s guidance, I decided to try it, and it quickly became a necessary piece of the puzzle.

1. Balance and Core Strength

Ballet places a tremendous emphasis on maintaining balance and alignment through the core and lower body. Every position—whether a plié, relevé, or arabesque—demands that you strengthen and stabilize your midsection. I found these paid dividends on the racecourse when shifting weight to keep the Laser flat and fast upwind and maneuvering through tacks and jibes.

2. Flexibility and Range of Motion

From deep knee bends to graceful leg extensions, ballet stretches muscle groups that traditional workouts can sometimes overlook. This extra flexibility allowed me to remain comfortable in the contorted positions one often finds oneself in during mark rounding or sudden weight shifts.

3. Body Awareness and Grace

Laser sailing may not look “graceful” from the outside, especially when you’re drenched and hiking hard, but the precision of your movements truly matters. Ballet taught me to be conscious of every part of my body—hands, arms, hips, legs, and especially my feet. Subtle shifts in body position translate directly into boat handling efficiency.

4. Discipline and Mental Focus

Ballet is highly technical; it demands unwavering concentration and repetition of the same moves until they’re second nature. That mental focus transferred seamlessly to the racecourse. I became more locked in under pressure, whether navigating a crowded starting line or making tactical calls in fickle breezes.

5. Psychological advantage. At first, I endured some good-natured ribbing from fellow sailors about my “pirouettes,” but the results soon spoke for themselves. My posture improved, and I felt more in tune with the demands of a strenuous, ever-changing environment on the water.

Designing a Sailor’s Training Program

Bill and I put together a routine that I followed religiously in the lead-up to the 1977 Laser World Championship:

Running (3–4 days a week, 3-5 miles)

Interval Training: Short bursts of high intensity followed by active recovery. This mirrored the high-output efforts needed when rounding marks or accelerating off the start line.

Long Distance: To build endurance, I would do a longer run one day a week.

It honed my breathing control, which is key when you are at the edge of your oxygen capacity on a windy upwind leg.

Strength Training (2 days a week)

Core Work: Planks, sit-ups, and balance exercises to maintain proper hiking posture.

Upper Body: Pull-ups, push-ups, and light weights with high repetitions for muscle endurance.

Legs: Squats and lunges for hiking strength and stability.

Ballet Sessions (6 days a week)

Focusing on balance, flexibility, and precision of movement is crucial for boat handling and tactical agility.

On-the-Water Practice (2 one-hour sessions a week)

Nothing replaces time in the boat. Short and sharp sessions fine-tuning boat handling—tacks, jibes, and mark roundings—while applying my newfound fitness and balance skills.

The Road to the 1977 Laser World Championship

The 1977 World Championships, held in Bouzios, Brazil, was heading for a showdown between myself, the 1976 World Champion, and Peter Commette, the 1975 World Champion, who didn’t attend the 1976 World Championship. Peter was a fierce competitor and trained under Joe Duplin, the famous college coach known for not leaving any stone unturned. Peter was undoubtedly the focus and the person to beat; we viewed this as a grudge match. He probably saw me as his primary threat.

Peter came out to San Francisco, where we trained together. Part of our training routine was running together from the St. Francis Yacht Club to the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge and back, approximately five miles. In these runs, no quarter was given to emphasize our competitiveness. There was a long section at the end of the run with a pair of gates, which we discussed as the finish line. With about a quarter mile to go, the pace quickened, and at the end, there was a full-out sprint. I won by a dozen or so strides, only to see him continue past the gate, claiming that he thought the finish line was at the Yacht Club, which was a further 200 yards - good times.

As the 1977 Laser Worlds approached, I felt a sense of confidence I had never experienced before. My energy levels stayed high throughout back-to-back practice sessions, and the precise movements honed through ballet training helped me maneuver the boat more fluidly. I could push aggressively on the start line, knowing I had the stamina and balance to handle the physical demands of the race.

As reported in an article published by the Laser Class magazine on the World Championship, specifically describing the finish of Race 3, with big waves and a lot of boats capsizing, as described by a member of the race committee - Craig Thomas positioned to cross me just short of the line to take second, and: “Bertrand never budged from his characteristically closed compact stance but could be seen sizing up each oncoming wave. Suddenly, without any visible sign of preparation, he exploded from a full hike into a flawless roll tack and accelerated a boat length to take Thomas by a foot.”

Bill’s presence as a motivator and strategist was invaluable. If I felt tired, he was there to remind me of the greater goal. He would say, “Laser sailing is about discipline—not just in tactics but in personal preparation.” Those words became a mantra, especially as the training sessions became more intense.

Triumph and Reflection

When I claimed my second Laser World title in 1977, I knew it was more than just a victory on paper. It was tangible proof that the cross-training approach—including a healthy dose of ballet—Bill Monti and I had developed could transform a sailor’s performance. On the water, I felt fresher, more agile, and more mentally focused than ever before. Even when conditions worsened, or the wind picked up, my body and mind were ready for the challenge.

Afterward, many people asked what had changed since my first world title. My answer was simple: “I finally learned to train properly for the demands of Laser sailing.” The synergy between Bill Monti’s holistic fitness program, my ballet training, and my time in the boat gave me the edge needed to stand on the podium again.

Lasting Lessons for Today

Nearly five decades later, cross-training is now widely recognized in sailing. Today’s champions in the Laser (ILCA) class and other dinghy and keelboat classes rely heavily on structured fitness programs. This evolution traces directly back to forward-thinking coaches and trainers like Bill Monti, who saw beyond the boundaries of traditional sailing practice—and embraced methods like ballet.

My journey reminds me that innovation often begins in the margins. Bill and I took what was then a cutting-edge approach—combining running, strength work, and, yes, ballet—and proved that it could make a critical difference in a notoriously tough one-design class.

I owe Bill Monti a great debt of gratitude. Without his keen insights and unwavering support, I might have remained a good Laser sailor but not a great one. Throughout that season of intense cross-training, calculated on-the-water practice, and a few pliés, I pushed beyond perceived limitations. Winning my second world title in 1977 was the crown jewel of our efforts—a testament to the power of training the body and the mind to excel in a demanding sport like sailing.

—John Bertrand (USA)